From 2001 to 2013, college enrollment in the US increased rapidly. Young people delayed the full-time work portion of their lives, ostensibly to seek skills for an evolving set of jobs. Trends since 2014, however, suggest that the increase in education is not an entirely structural change. Over the past few years, a tighter labor market has been leading more young people to full-time work, suggesting that a weak labor market, rather than simply concern over a changing set of jobs, was pushing some young people to enroll from 2001 to 2013.

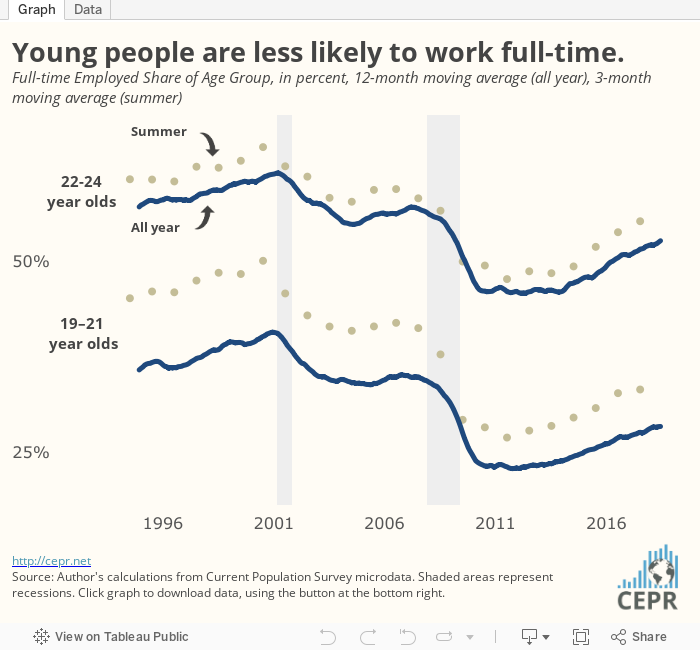

The Current Population Survey shows that from 1994 to 2001 young people were increasingly taking full-time jobs. By March 2001, an annual average of 40.5 percent of people age 19 to 21, and 61.5 percent of people age 22 to 24, were employed full-time. Following the recession of 2001, the trend reversed completely. By March 2013, an annual average of only 23.3 percent of those age 19 to 21, and 46.0 percent of those age 22 to 24, had full-time jobs (figure below).

While data show a long-term decrease in full-time employment among younger people, the same data also show two signs that a weak labor market plays a role. First, the full-time employed share of both age groups has increased steadily since 2014. As of the year ending in June 2018, 28.3 percent of those age 19 to 21, and 52.6 percent of those age 22 to 24, are employed full-time.

Second, if education were driving the change in youth employment then summer youth employment would increase relative to school year employment. Since most US schools offer students a summer break, the share of young people employed full-time during June, July, and August is much higher than at any other point during the year. If young people are opting for school because of abundant attractive new jobs, then summer break might provide an increasing chance for full-time employment for those in school during the rest of the year. However, summer full-time employment has actually fallen relative to school year employment, suggesting the opposite, that young people are having a harder time obtaining summer jobs compared to the period from the mid-1990s through 2001.

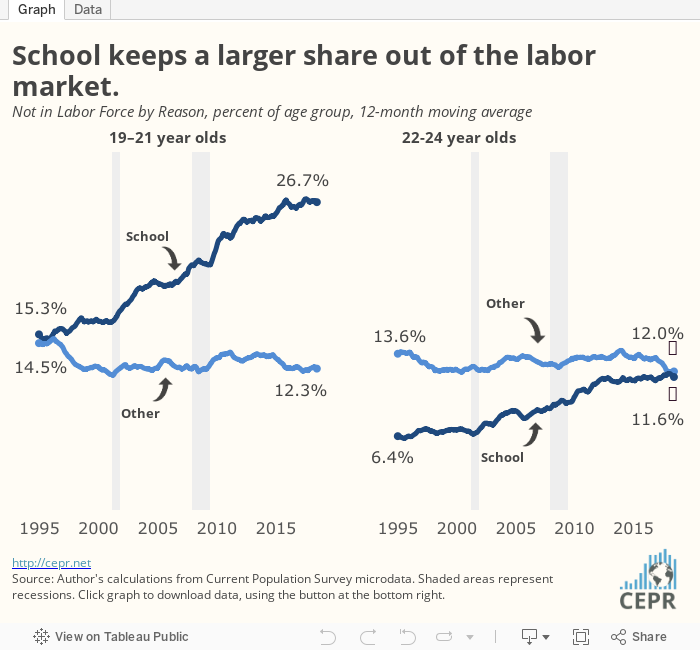

The weak labor market therefore plays a role in encouraging school enrollment; those who are able to do so can wait out a poor set of job opportunities while gaining new skills. It’s important to note, however, that the tighter labor market since 2014 seems to have slowed, but not reversed, the previously rapidly increasing share of young people who are not in the labor force, and do not want a job, because they are enrolled in school (figure below).

In 1994, for about half of those age 19 to 21 who are not in the labor force (meaning they are not employed and have not been looking for work) the reason was school enrollment. The rest are often staying home to take care of family, disabled and unable to work, or sometimes believe that there is no job available. Since then, school enrollment has rapidly increased labor market nonparticipation. By the year ending in June 2018, more than two-thirds of nonparticipation is due to school enrollment. Among those age 22 to 24, the rate climbs from about one-third in 1994 to about one-half in the latest year of data. School-related nonparticipation growth among the slightly older cohort has largely stalled since 2013, while growth has slowed some among the younger group.

To sum up, much of the overall drop in full-time employment among young people comes from school enrollment. At least some portion of school enrollment was motivated by the particularly poor quality of the labor market during the years from 2001 to 2013, with students hoping to emerge from school with skills that make them more competitive, and at a time when job applicants have more bargaining power. It remains to be seen whether the labor market will continue to tighten and how full-time employment and school enrollment will respond among younger people.