WANG JIANQIN, in a thick red jerkin worn over her working clothes, does not look like an agent of superpower reprisal. The 60-year-old farmer rears 4,000 pigs in a brick-walled compound in Shunyi district, some 45km from Beijing. About a fifth of the food that she uses to fatten them up is soyabean meal, something China has come to import in vast quantities from the American Midwest.

Over the past 30 years, as the demand for pork in China has outstripped that in any other country, Ms Wang and her peers have done very nicely out of that American soya. And in America farmers have done well out of Ms Wang. Chinese money helped them pay for lots of cheap, Chinese-made goods at Walmart—as well as for the genetically modified seeds and other high-tech inputs stuffed with American know-how that make them so productive.

But this year their earnings will be a good bit down. In April President Donald Trump accused China of stealing intellectual property, coercing American firms into technology transfers and other unfair trade practices. Mr Trump spent a dizzying spring and summer announcing punitive tariffs, expanding their scope and amping up their severity. There are now tariffs of between 10% and 25% on $250bn of imports. Mr Trump has growled his willingness to go up to 25% on all of those goods and start in on the remaining $267bn if he does not get his way.

When China punched back, announcing tariffs on up to $60bn of American imports, it included a 25% tariff on soyabeans to hurt farm states that had voted for Mr Trump, such as Iowa. Despite China’s president, Xi Jinping, having fond memories of the time he spent in Muscatine, Iowa, in 1985, the fact that the state is both second among America’s soyabean producers and disproportionately influential in American politics makes it a prime target. Ms Wang was weaponised. As the price of soya has shot up, she says, some of her peers have switched to other feed, and she is thinking of following suit. The Chinese Feed Industry Association has proposed new standards for pigfeed that cut the soyabean content to just 11-13%—a change that could reduce annual consumption by 10m tonnes.

China wants to do a deal. But America may want more than it is willing to give, because its concerns are wider than trade. Mr Trump sees himself leading a fight against “globalism”, by which he means any order that binds American sovereignty, or fails to put American workers first. As he put it to the UN General Assembly in September, “We reject the ideology of globalism and we embrace the doctrine of patriotism.” And his great patriotic fight is with China. “When I came,” he said in August, “we were heading in a certain direction that was going to allow China to be bigger than us in a very short period of time. That’s not going to happen any more.”

A broadly based interdependence ties Beijing’s pigs to Iowa’s fields, interweaves supply chains and distribution networks across the Pacific and has seen copious Chinese investment in America. That had, until recently, led observers in both China and America to think attitudes like Mr Trump’s could be nothing but bluster. Though relations might be testy from time to time, the economic logic which favoured getting along was simply too strong to ignore. But American unease about China’s growing technological heft, increasing authoritarianism and military strength is now overriding that logic.

America is undergoing a deep shift in its thinking about China on right and left alike. There is a new consensus that China has a deliberate strategy to push America back and impose its will abroad, and that there needs to be a strong American response. The coalition takes in conventional free-traders in the White House as well as the zero-summists in Team Trump and the national-security hawks in Congress. Pentagon chiefs and the bosses of spy agencies have framed China as the greatest threat to America’s security, requiring a “whole of government” response. In civil society, the coalition includes religious conservatives, human-rights advocates, labour unions and old-school protectionists.

On October 4th Vice-President Mike Pence hammered the new attitude home in a de facto declaration of cold war. As well as decrying China’s internal repression and its surveillance state, he inveighed against its attempts to hack and bamboozle America: it was employing “political, economic and military tools, as well as propaganda, to advance its influence and benefit its interests in the United States.” One example: a supplement in the Des Moines Register, Iowa’s newspaper of record, which China paid for in an attempt to turn Ms Wang’s American suppliers against the administration’s trade policies.

Given Russia’s blatant attempts to interfere in the election that brought Mr Trump to power, one could be forgiven for rolling one’s eyes at this stressing of the mote, as opposed to the beam. But Mr Pence levelled charge after charge, hinting, without supplying evidence, at darker interference. He deplored the China-friendly programmes supplied to dozens of American outlets by Chinese state radio. He accused China of exerting pressure on American universities by threatening to deny visas to researchers, and bribing and bullying Hollywood into portraying it in a positive light.

The vice-president accused the Communist Party of obtaining “American intellectual property—the foundation of our economic leadership—by any means necessary”. It would feed this into its “Made in China 2025” plans to dominate advanced industries such as robotics, biotechnology and artificial intelligence. He decried its intimidation of Taiwan, which China believes to be a rogue province, and its broad military ambitions. China, he said, “wants nothing less than to push the United States from the western Pacific and attempt to prevent us from coming to the aid of our allies.” This would not stand. The Trump administration, Mr Pence said, “has now pledged to fight back hard on all fronts—and win.”

This is not just a war of tariffs and words. In early October Xu Yanjun, a functionary of China’s foreign-intelligence agency, was lured to Belgium and then extradited to America on charges of stealing trade secrets from American aerospace companies. It is the first time a Chinese national has been extradited to America for such spying. A few days before that, in what a spokesman for America’s Pacific fleet called “a series of increasingly aggressive manoeuvres”, a Chinese destroyer came within 40 metres of an American guided-missile destroyer, the USS Decatur, which was on “freedom of navigation operations” within waters China stakes a claim to on the basis of a couple of disputed reefs nearby. Warships acting like dodgems feels like an escalation.

The ship that foundered

In an ocean of mistrust, it is worth recalling what still holds. The two countries’ bilateral trading relationship remains the world’s biggest, despite the trade war. The Chinese diaspora and 350,000 Chinese students in American colleges and universities mean there are a great many personal ties between them. China co-operated in harsh sanctions aimed at getting North Korea to restrain its nuclear programme. Some progress has been made in cracking down on the flow of Chinese opioids to America. And it is not as if the two countries are fighting proxy wars in third countries. This is not—yet—a cold war like the previous one.

But genuine, if sometimes wary, engagement has been replaced by frank talk of strategic competition and deepening mistrust underlined by big tariffs. As Kevin Rudd, a former prime minister of Australia now running the Asia Society Policy Institute, a think-tank, puts it, the ballast that once kept the relationship on an even keel has been jettisoned. What went wrong?

The original ballast, the steadying factor which allowed Richard Nixon’s opening to China in the 1970s, was a shared strategic mistrust of the Soviet Union. America’s underpinning of East Asia’s security gave China the confidence to begin its opening up to the world in the late 1970s. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a shared dislike of it was no longer much of a basis for a relationship—especially as the overtly pro-American tone of students in Tiananmen Square in 1989 had made the party afraid that America was bent on toppling communism there, too. But gradually, over the 1990s, the two sides found a new way to steady their relationship: trade.

The era of closest alignment was the early 2000s, after America helped China become a member of the World Trade Organisation. China had been building up its armed forces since the Taiwan Strait crisis in 1996, when a show of naval force by President Bill Clinton brought Chinese missile tests designed to intimidate the Taiwanese to an abrupt halt. But China was not in a position to mount a serious regional challenge to America—where concern about its rapid rise was tempered by an assumption among political and business elites that the rapid expansion of its middle class would bring some measure of liberalisation. It was not just Westerners who imagined that an authoritarian China might liberalise internally and become a “responsible stakeholder”, in the phrase an American diplomat, Robert Zoellick, used in 2005. Many Chinese argued the case, too.

There were incidents that raised tensions, such as the forced landing of an American spy plane on Hainan after a collision with a Chinese fighter in 2001. But neither side saw an attractive alternative to getting along.

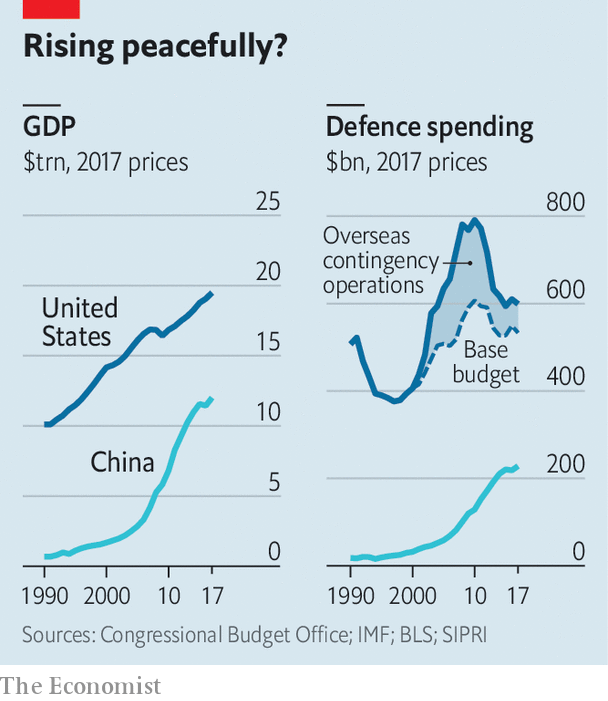

Then two things changed. The global financial crisis narrowed America’s economic lead. After the collapse of its export markets threw some 20m Chinese out of work in just a few months, the government responded with a massive stimulus, rolling out high-speed rail, motorways, sewage-treatment plants, housing projects and more. Chinese GDP bounced back; America’s growth remained well below par for years, seemingly justifying a certain technocratic cockiness, as well as a degree of Schadenfreude. In 2006, measured in current dollars, America’s economy was five times bigger than China’s. In 2017 it was just 60% bigger (see chart).

The second change was Mr Xi. His ascension in 2012 began what Chinese officials now call “the new era”. He celebrated and sought to entrench the state’s leading role in the post-crisis economy. He stifled dissent and tightened the authoritarian screws. His new-era China loaned vast sums to governments with dodgy records on everything from human rights to corruption and the environment. Its Belt and Road Initiative and the lending institutions that support those infrastructural ambitions, along with its talk of “reform of the global governance system”, make it plain to Mr Rudd that China is not embracing the American-led global order. It is seeking to change it—at precisely the time that America, under the anti-globalist Mr Trump, is giving up on its support.

American concern over those changes has been exacerbated by a generational shift in its bureaucracy. Douglas Paal of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington think-tank, points out that the public servants who knew China as a poor country and saw the fruits of it opening in the 1990s are retiring. Whether they be the kindly folk who administer development aid or hard-boiled China-hands at the Pentagon or CIA, the younger officials now running China policy have known only a wealthy, powerful nation breaking promises of reform. In 2014 many also saw their own sensitive data, sometimes including information about love lives, drinking habits and finances gathered for security clearances, stolen by Chinese cyber-thieves from the Office of Personnel Management. “That makes the risks personal,” says Mr Paal.

Such malfeasance continues. On October 9th CrowdStrike, an American computer-security company, published a report into intrusion attempts it had monitored, identifying China as the most prolific source of nation-state attacks on American computer networks in the first half of 2018. The firm cited evidence of China-based hackers attacking firms in biotech, aerospace, mining, pharmaceuticals, professional services and transport. Foreign diplomats and Western businessmen say that Chinese intruders frequently target sensitive commercial data held within servers in China and even Western home countries. The agreement between Mr Xi and Barack Obama in 2015 that China would refrain from state-sponsored intrusions to steal commercial intellectual property is clearly in poor shape. Controls on Chinese investment in American tech businesses are tightening up.

The Chinese government’s response is to declare its support for cyber-security and the protection of intellectual property, though American firms which have had their technology snaffled say that Chinese courts make no pretence of upholding the same law for all. On October 15th the state news agency, Xinhua, published a commentary calling America “a cyber-predator that has a notorious record of violating other countries’ interests and rights.” The country’s ulterior motive was “fearmongering” against China, it said, citing the “eye-popping” revelations made by Edward Snowden, a former American cyber-spy turned leaker who revealed how America’s National Security Agency used hacking techniques and hidden vulnerabilities in high-tech kit to eavesdrop on America’s foes—including China—as well as its friends. Xinhua also accused America of “slandering” Chinese high-tech enterprises such as Huawei, a telecoms giant, in order to “stir up Sinophobia in other countries so as to browbeat or hoodwink them into blocking Chinese competitors and saving the market for US companies.”

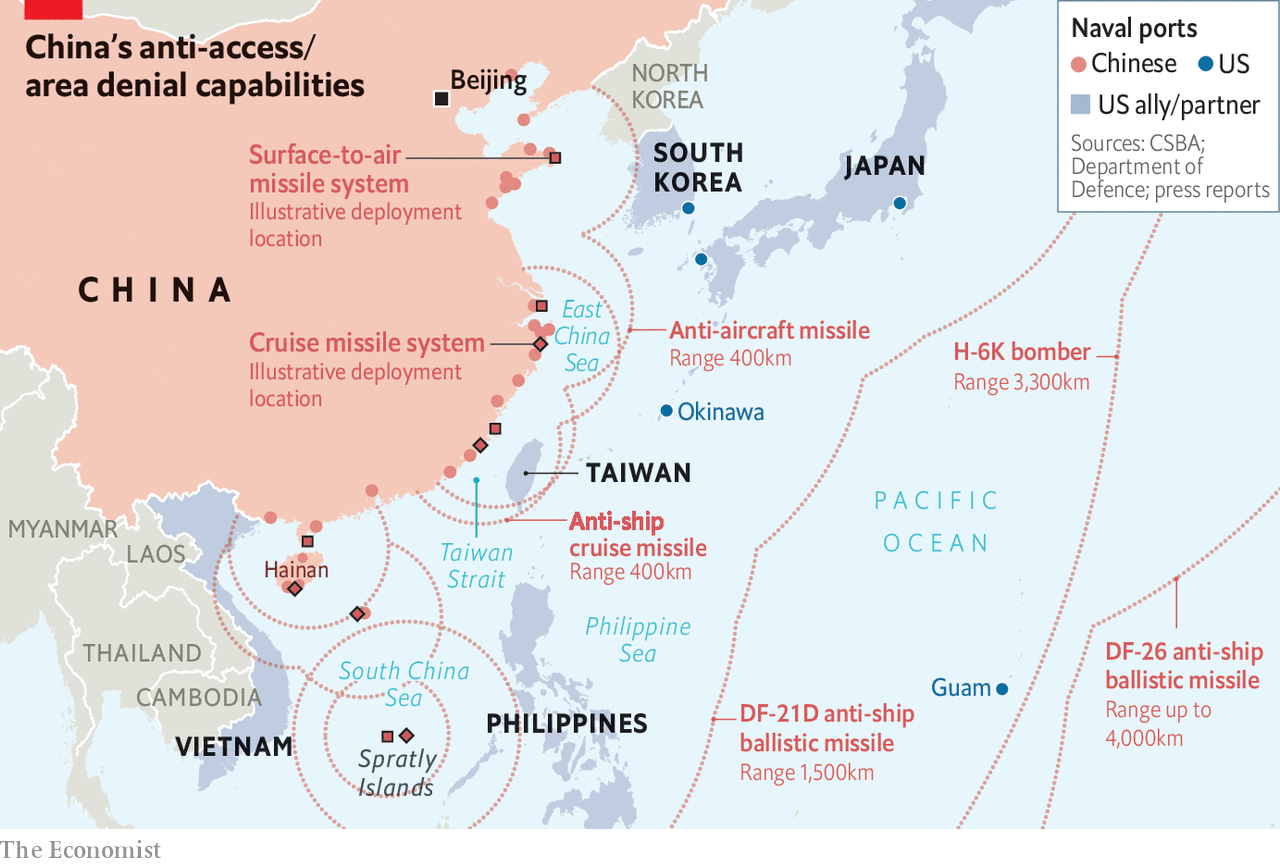

China is also becoming a new source of competition on the high seas, its warships increasingly active from Djibouti on the Horn of Africa, where China has established its first overseas base, to the East China Sea, where America is treaty-bound to protect disputed islands controlled by Japan. Last April China’s largest-ever naval exercise saw scores of ships in the Taiwan Strait. China has also been picking away at the dwindling number of states that maintain official relations with Taiwan.

Raising the stakes

China’s military spending has not changed much as a share of GDP; but when your GDP is as large as China’s, and growing as fast, you can afford to buy a lot of arms. The International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank, notes that since 2014 China has launched naval vessels “with a total tonnage greater than the tonnages of the entire French, German, Indian, Italian, South Korean, Spanish or Taiwanese navies”. What is more, the increasing number of its ships may well understate the rate at which China is improving its ability to sink enemy vessels. China’s anti-ship missiles, launched at sea, in the air or from the ground, are more plentiful and more advanced than America’s, and some boast longer ranges, too; the same goes for some of its other munitions. That, according to Eric Sayers, who until recently was a consultant at America’s Indo-Pacific Command, is what America’s planners need to worry about.

A growing array of satellites and sensors, including some on disputed islets, can funnel panoptic targeting data to this wide array of missiles, making it dangerous for hulking American aircraft-carriers to station themselves near flashpoints. “In any air war we do great in the first couple of days,” says Christopher Johnson, formerly the CIA’s senior China analyst. “Then we have to move everything back to Japan, and we can’t generate sufficient sorties from that point for deep strike on the mainland.” If America cannot destroy missile sites on the mainland it risks incurring severe losses in any fights near Chinese shores.

America does have one thing that its rival does not: friends. Many of these, including India, Japan and Taiwan, are glad to see it dispensing with old niceties and calling China a strategic competitor. America, India and Japan hold annual exercises that grow more ambitious by the year, flying aircraft off one another’s decks and sharing tips on how to hunt unfriendly submarines. An intelligence-sharing agreement between America and India, which Indian leaders had kept on ice for years, was signed in September, paving the way for more advanced weaponry to flow to India’s armed forces. America and Australia have both sounded out Papua New Guinea on the prospect of new bases in the southern Pacific. The “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance, in which America, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand freely share the fruits of their eavesdropping, has been energised by joint efforts to track China’s interference in foreign countries.

In fractious times, it is good to talk. Yet lines of communication between America and China are shutting down just as they are most needed. A high-level diplomatic and security dialogue between the defence ministers of America and China, hailed as a “pillar” of the relationship when it was launched last year, was abruptly junked by China last month, after its armed forces fell foul of American sanctions on buying Russian arms. China has also curtailed or cancelled several other military contacts between the countries—not that these have ever been extensive or especially fruitful. A lower profile Military Maritime Consultative Arrangement, in which each side swaps complaints about encounters like that in August, continues to function. Were that to now be abandoned, alarm bells should really start ringing.

Tensions between the two powers have risen before—but only when there has been a crisis, as in the Taiwan Strait in 1996 or on Hainan in 2001. What is alarming is the degree to which they have heightened without any such flashpoint. Now that the relationship’s ballast has been largely jettisoned, future squalls will be even scarier.

Chinese caution might offer some hope. Officials in China are remarkably casual, even dismissive, about the idea that the country’s behaviour played any role in stoking today’s tensions (see Chaguan). But they still hope to de-escalate the trade war. This is why, though Chinese media routinely call America a bully, and treat its complaints against China as false pretexts for strategic containment, the taps of nationalist outrage have not yet been cranked fully open, and communist propaganda chiefs have not launched a personal campaign against Mr Trump. If the Chinese public has been taught to see the American president as their foe, it is harder to cut a bargain with him.

Self-fulfilling prophecies

Economic officials in China insist their country remains committed to open markets. Li Wei, head of the Development Research Centre at the State Council, China’s cabinet, sets out clearly that this is for reasons of self-interest—a shrewder tactic than merely mouthing pieties about Chinese benevolence. China must continue to open and reform its economy, he says, because of its own development needs. Recalling the phrase of China’s paramount leader in the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping, that opening a window to the world would bring in both fresh air and a few flies, Mr Li says that “people generally find that there’s quite a lot of fresh air that came in with reform and opening up, not a lot of flies.” He insists that if China punches back on trade, it should be seen as aggression in defence of globalisation, not a rethinking of China’s commitment to open to the world.

But an ambition for further development is hardly going to placate America. Take the Made in China 2025 initiative unveiled in 2015 by the State Council and filled with references to “indigenous innovation” and self-sufficiency in high technology, a cause that Mr Xi has made his own. Though Chinese diplomats now downplay the plan’s importance—lamenting that, intended for domestic consumption, it has become a focus for international concern—it was enshrined in the central government’s latest Five Year Plan, approved last year. A study undertaken by the European Chamber of Commerce in China in 2017 that tallied up central and local government announcements found hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies, research funds and other forms of support. In sectors from electric vehicles to industrial robotics, foreign firms face pressure to hand over core technologies to Chinese joint-venture partners, merely to keep market access. Mr Pence fumes that “Beijing now requires many American businesses to hand over their trade secrets as the cost of doing business in China.”

The charge that America would not tolerate China growing larger under any circumstances used to be something of a fringe view in Beijing. Now there is a debate at the top of the government as to whether it is in fact true, and that America has become a foe so implacable that there is no point making concessions to it. That atmosphere makes it harder to avoid a deeper trade confrontation. Even if Mr Trump surprises the world once again and settles for a deal over trade that he can tout as a win, the mood of competition over regional security could bring tests of strength on the seas and in the sky, as well as miscalculations and possible clashes.

Well-connected scholars and retired officials have shared their concerns with Western contacts about a febrile mood within China’s national-security establishment. They detect genuine excitement over the prospect of a great-power contest in which China is one of the protagonists. This coincides worryingly with the squeezing of public space for discussion. Scholars are not now supposed to debate foreign policy in the open, and strident nationalists dominate what debate there is. Even the idea of an expensive arms race with America strikes some Chinese experts as a fine plan, given their confidence in the long-run potential of their economy. In this dangerous moment, blending grievance and cockiness, it seems astonishing to remember that less than a generation ago Chinese leaders assured the world that they sought only a “peaceful rise”.